This is no fairy tale though. One hundred years ago, that player was Walter Hagen, and one of his most important triumphs occurred at Hoylake.

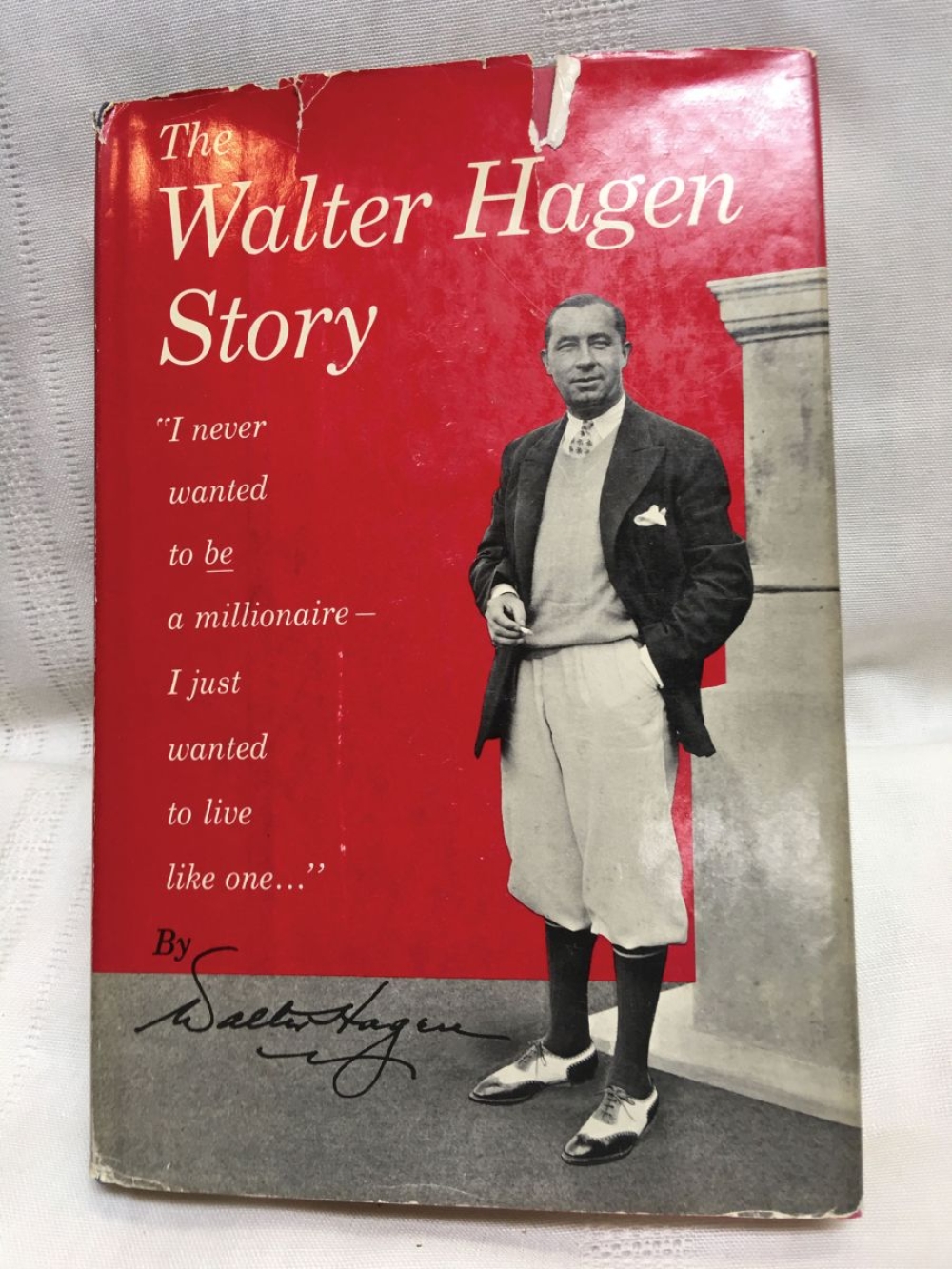

Hagen was the first American golf superstar. His on-course success, including wins in the 1914 and 1919 U.S. Opens, had cracked open the door to fame, but his personality and hutzpah broke it down. At clubs around the world, he took the touring professional from the car park to the ballroom. The game’s first great showman, he was the first player to make real money, and the first to spend like he made even more. He became just as famous for his off-course frivolities, some of them embellished, some underplayed. “Walter broke 11 of the 10 Commandments,” famed golf promoter Fred Corcoran often said.

How big a star was Walter Hagen? He didn’t have one nickname, he had two: The Haig and, even more appropriate, Sir Walter. But by the summer of 1924, the 31-year-old’s place atop professional golf was unsteady. The previous year had been a season of seconds in the big events. Then, in early June, he finished tied for 4th in the U.S. Open at Oakland Hills, putting a ball in the water on the infamous 16th hole and taking a double bogey in the final round.

Just three days later, Hagen and his second wife Edna (married just over a year, although it would last only three more) sailed out of New York City for Southampton on the Mauretania. Their final destination: The 59th Open at Royal Liverpool.

Walter broke 11 of the 10 Commandments.

The Open might well have been his favorite event, where the strengths of both his golf game and social skills could be fully displayed. In 1922, Hagen became the first American-born champion by winning at Royal St. George’s in just his third try. The next year at Royal Troon, he finished one behind the champion Arthur Havers who holed a bunker shot on the 72nd hole. In between, he charmed his way through the upper echelon of British society, befriending the eventual King Edward VIII himself.

Where Hagen went, others followed, including the top American-born players. Gil Nicholls, Johnny Farell, Al Espinosa, and newlywed Gene Sarazen all made the seven-day journey across the Atlantic as well – the most to enter The Open up to that point. Scotsman Macdonald Smith and Englishman Jim Barnes, both now U.S. citizens, traveled as well.

One player of significance who did not make the trip: the 22-year-old amateur sensation Bobby Jones. His wedding to Mary Malone was scheduled for June 17 in Atlanta with a subsequent honeymoon in the mountains of North Carolina. Jones had played his very first competitive rounds in the United Kingdom at Hoylake in the 1921 Amateur (he would take advantage of another opportunity over the Royal Liverpool links six years later).

Even with his first and second place finishes the previous two years, Hagen wasn’t the odds-on favorite heading into this championship, only fourth at 10-to-1. The rivalry between American and British players was a constant storyline between the wars, and English money favored defending champion Arthur Havers (4-to-1), George Duncan (4-to-1), and Abe Mitchell (8-to-1).

The Hagens settled into the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool, and Sir Walter’s initial trips out to Hoylake were encouraging. American newspapers delighted in reports that he had shot a 68 in a practice round. The layout had been recently renovated by Harry Colt and was now a stout 6,750 yards in length. Every hole received a tweak, but the most significant alterations were along the Dee Estuary with new greens and reconfigured routings of the Alps, Hilbre, and Rushes.

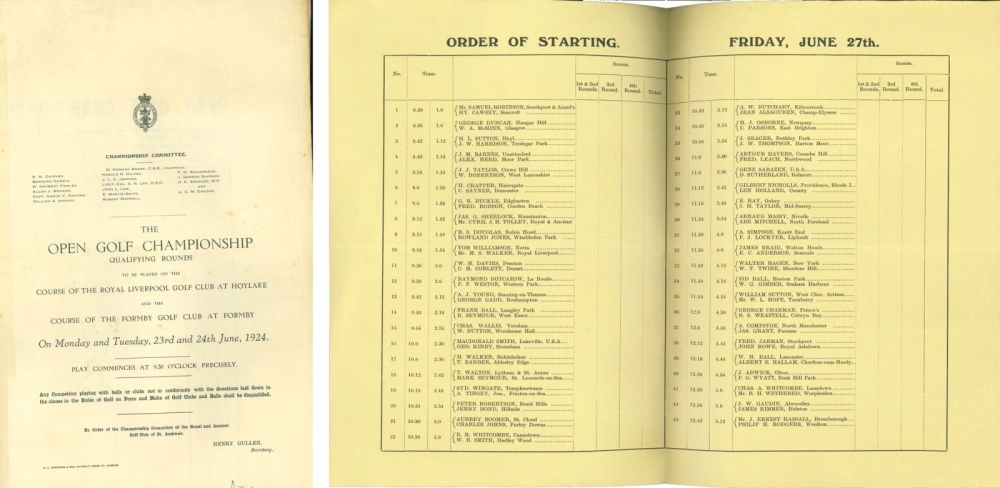

Still, Hagen, as well as the entire field of a record 277 entries, had to first progress through two qualifying rounds. Nothing was guaranteed as Sarazen could attest. He had missed the previous year as the reigning U.S. Open champion.

It seemed as if Hagen might follow suit. In the first round at Hoylake, he started by three-putting the 1st hole and then made a seven on the 2nd after floundering in the rough and losing his ball in gorse. Constantly in trouble, his woes were compounded by several uncharacteristic short misses. He shot an 83. Nevertheless, he didn’t appear concerned as The New York Times reported he “walked away with his wife seemingly not bothered and with an air of confidence that everything would turn out all right tomorrow.”

Indeed it did the next day at Formby, although after a shaky start as Hagen and Jim Barnes were late for their tee times due to a delayed train from Liverpool. On the 7th, Hagen holed out from more than 50 yards for a three. A flawless eight-hole stretch on the inward nine produced a 73 and ensured he was one of the 86 players who qualified for the championship proper, albeit by just two strokes.

The headline of qualifying, however, was five-time Open champion J.H. Taylor, medalist by four strokes as a result of a competitive course-record 70 at Hoylake. The feat on its own was remarkable but even more so considering Taylor was now 53 years old.

I threw my putter in the air and never saw the ball or putter again.

The championship started two days later with 72 holes contested in nearly 36 hours. The always dapper Hagen arrived dressed in a lavender sweater and knickers off-set with black and white shoes, but his play was inconsistent, shooting rounds of 77-73. After 36 holes, he was in a tie for third place, three back. Taylor continued his strong play from qualifying and sat in second place at the midway mark. They all trailed Ernest Whitcombe. The oldest of the famed trio of brothers from Somerset had shot a course-record tying 70 in the second round – 10 shots below the scoring average that afternoon and the lowest round of the championship by three strokes.

The next day, championship Friday, the mighty breezes of Hoylake finally blew. Now outfitted more subtly in gray with white shoes, Hagen shot a 74 in the third round. That wound up being the best score of the morning and jumped him into a tie with Whitcombe for the 54-hole lead.

In the afternoon, the Englishman went out an hour and six minutes before Hagen. Both struggled on the outward half. Whitcomb shot 43; Hagen a 41 with sixes at the 1st, 3rd, and 8th holes.

But Whitcombe righted his game and came home in an impressive 35 to finish at 302. George Duncan, Macdonald Smith, Frank Ball, and Taylor were in contention before fading away over the closing holes. That left Hagen as the only challenger, and when he found out Whitcombe’s final total early on his final nine, he knew he needed level-fours the rest of the way to win.

His long shots were all over the place, but hole after hole, Hagen relied on his vaunted short-game and ever-sure putting, not to mention his temperament and fortitude. Even in dire trouble at two of the new holes, he produced heroic shots to get up-and-in after a sliced approach shot on the 12th and a bunkered tee shot on the short 13th. Hagen seemed to summon his best results when he had no other recourse.

By the 17th hole, the title was in sight as Hagen stood slightly off the fairway. With Stanley Road looming right and behind the green, he made a daring decision. In recalling the scene, Sarazen wrote, “Hagen is the only golfer I know who would have passed up the safe route to the green and risked the championship by going straight for the flag.” His mashie approach barely cleared the front left bunker and finished some 12 feet away for another sure four.

That left Hagen needing one more four on the 72nd hole. In the fairway with his best drive of the day, he let his second shot ride the wind, and his Spalding ball finished in a clump of clover over the green. The return chip came up six feet short of the hole. He took nearly a minute to survey the putt before taking his stance.

The most thrilling scene ever depicted in the movies pales into insignificance…

“I stroked the ball…gently but firmly,” wrote Hagen. “It righted the last turn, straightened out and headed for home! I threw my putter in the air and never saw the ball or putter again. But I sure saw that Open trophy.”

In Golf Illustrated, George Greenwood proclaimed, “No more dramatic and no more thrilling finish to a championship has ever been witnessed on any links…The most thrilling scene ever depicted in the movies pales into insignificance before it.”

Home in 36 and a second Claret Jug in three years, Hagen’s fighting spirit had enthralled the gallery of 10,000-plus as they carried him off the green while singing his name. He had become the first person to win both the U.S. Open and The Open twice.

From nearly every quarter, newspapers and magazines proclaimed Hagen the best golfer in the world…and maybe the best ever.

Sir Walter would agree it’s a triumph still worth celebrating a century later.

Gil Capps is Editorial Advisor for NBC Sports’ golf broadcasts and author of The Magnificent Masters.