Forensic examination, which curiously had not been carried out before all the deals were struck, quickly proved that a red-faced Professor Trevor-Roper had been wrong, and those who had been sceptical from the off, were right. The diaries were very fake news. If nothing else, the fictional Fuhrer revealed that a literary hoax could fire imaginations and make money, and that forgeries had to be sophisticated if they were to outwit scientific tests. It was 1992 when the supposed diary of James Maybrick came to light. The story goes that a Liverpool scrap metal dealer called Michael Barrett had been given a Victorian journal by a friend - a journal kept by Jack the Ripper more than a century before, and which had been found beneath floorboards during renovations of Maybrick’s former home, the gothic and gloomy Battlecrease House in the Aigburth area of the city.

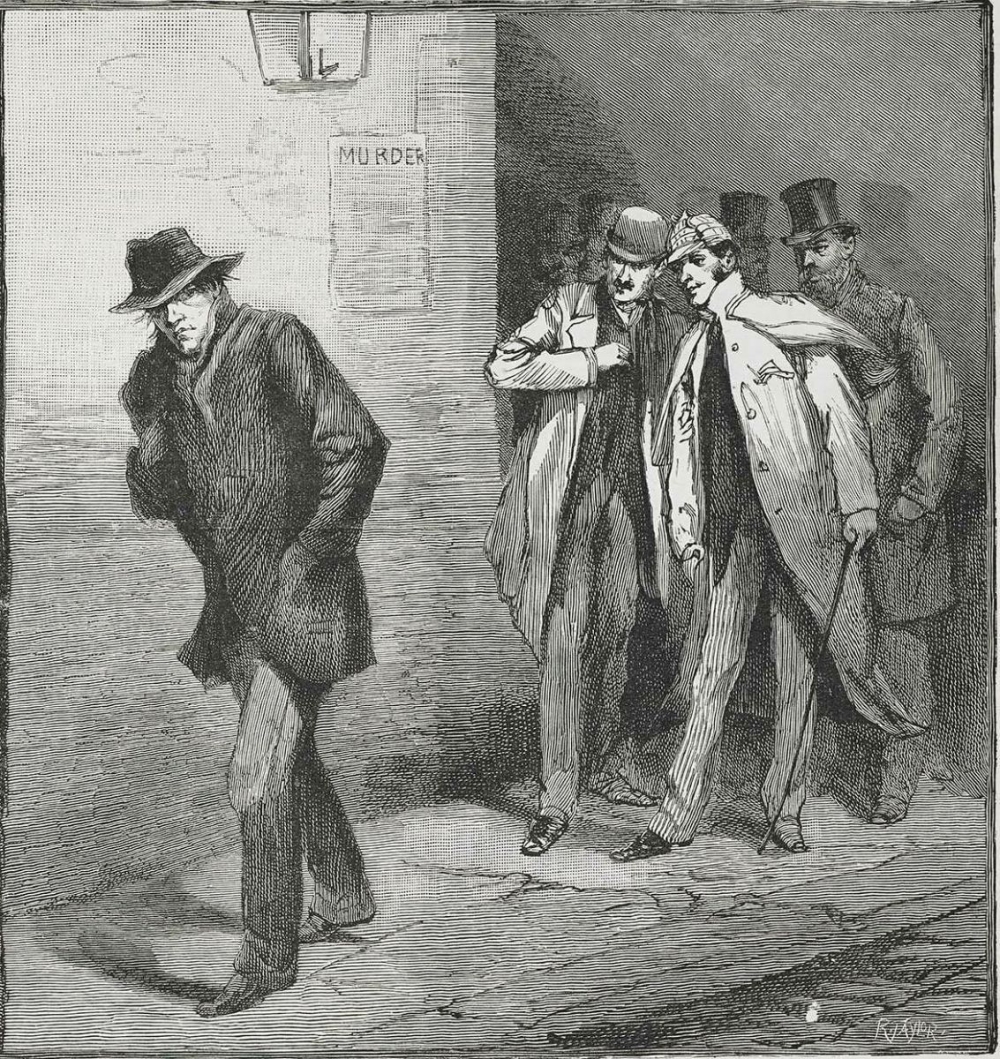

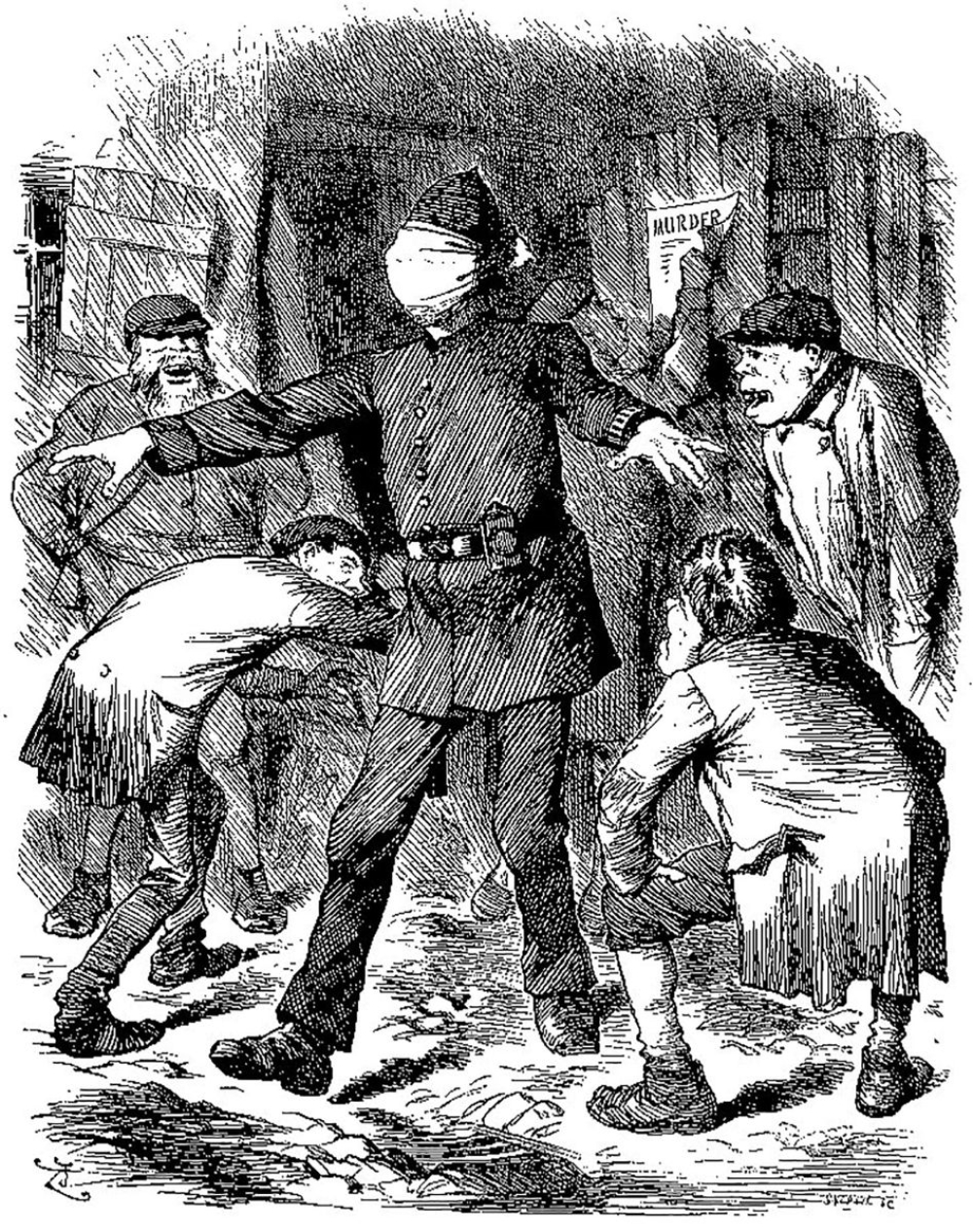

Although James Maybrick’s name was nowhere to be seen on the pages, there were enough clues strewn throughout the text for readers to conclude the author was him, the Liverpool born businessman and father of two children, a boy and a girl. Between August 31 and November 9 1888 a serial killer terrorised the Whitechapel section of London’s East End. Five women, all sex workers, were brutally killed and all but one of them were mutilated. She, the police concluded, was saved from defilement when her killer was interrupted and made off. During this horrifying spree, several letters - most if not all of them hoaxes - were received by the press and police. One beginning ‘Dear Boss’ mocked the authorities, promised more murder, and was signed ‘Jack the Ripper’.

James Maybrick was a cotton broker and founding member of Royal Liverpool Golf Club.

The name was the stuff of headlines and it stuck. The Ripper, who may have killed more women than those now known as the ‘canonical five’, was never caught, and more than a century later armchair detectives strive to identify him and argue the merits of suspects who have cropped up over the years. Among these are journalist Francis Craig, artist Walter Sickert and a Russian born barber called Aarron Kosminkski.

James Maybrick, a cotton broker and founding member of Royal Liverpool Golf Club, joined this list thanks to the mysterious diary. Written in a Victorian photo scrapbook with the first 40-odd pages torn out, it appeared to some to include details of which only the Ripper and the police could have been aware, while the account of what it was like to be a 19th century arsenic addict had a powerful ring of authenticity about it.

Maybrick’s struggle with the drug was well known, particularly in Liverpool where a sensational and widely reported trial had concluded that he himself was a victim of murder following an overdose administered by his wife, Florrie.

The 1871 Census places James living in Liverpool with his mother at 77 Mount Pleasant. His occupation is described as ‘commercial clerk’. A couple of years later he set up Maybrick and Company, Cotton Merchants. Business involved regular travel to the United States and, in 1874, he settled in Norfolk, Virginia, to open up an American branch. He contracted malaria, was given medicine that contained arsenic, and became hooked on it for the rest of his life.

On the boat back to Liverpool in 1880 he was introduced to the much younger Florence ‘Florrie’ Chandler, the petite and pretty American daughter of a banker, and romance bloomed quickly. They were married the following year. She was 18 or 19, he was 42.

Maybrick divided his time between Britain and the US and was no stranger to an extra-marital affair, fathering several children during a long, clandestine relationship with another woman. Perhaps in retaliation, Florrie took up with another, younger and better looking cotton businessman called Alfred Brierley. This tangled web has encouraged some to think Florrie’s infidelity drove her husband homicidally mad - and explains why the letters FM, written in blood, can be seen on a wall in a November 1888 police photograph of the body of Mary Jane Kelly, generally believed to be the Ripper’s last victim. There are bloody marks on the walls, ghastly ones, but seeing Florrie Maybrick’s initials there has the ring of what psychologists call motivated perception.

Crucially, James Maybrick was a regular visitor to London. At the end of April 1889 his health began to fail and he died a fortnight later. Foul play was mooted and an inquest concluded that arsenic poisoning was the likely cause. Suspicion fell on adulteress Florrie, and the case made against her was more about her morals than the hows and whys of the alleged murder of her addict husband. After a long and chauvinistic summing up by the judge, a guilty verdict was returned and Florrie was sentenced to death. The fairness of her trial was questioned, and her sentence commuted to life imprisonment. She was released in 1904.

.jpg_32806d83174ce8c193148d232eee6ebf.jpg)

As for the ‘diary’, it begged simple questions: why would James Maybrick, well to do, write in a scrapbook? (The kind of book picked up easily from a flea market or auction a century later.) Didn’t the handwriting in Jack’s ‘diary’ look more contemporary than Victorian? An opinion supported helpfully by Michael Barrett in 1995 when he admitted he had dictated the entries to his wife, Ann - though later he retracted this sworn statement.

However, scientific tests to date the ink used proved inconclusive.

The same is true of the pocket watch which - remarkably and, some believed, conveniently - turned up in 1993 in Wallasey on the other side of the river Mersey from Liverpool.

The watch was presented to the world by the late Albert Johnson. The signature ‘J Maybrick’ is scratched on the inside of its cover together with ‘I am Jack’ and the initials of the ‘canonical five’.

On the face of it this looked like a simple case of copycat counterfeiting aiming to cash in on the interest surrounding the diary, published the same year. But a report drawn up after the watch was scrutinised by electron microscope at the University of Manchester stated: “It must be emphasised that there are no features observed which conclusively prove the age of the engravings. They could have been produced recently, and deliberately artificially aged by polishing, but this would have been a complex multi-stage process.

“Many of the features are only resolved by the scanning electron microscope, not being readily apparent in optical microscopy, and so, if they were of recent origin, the engraver would have to be aware of the potential evidence available from this technique, indicating a considerable skill and scientific awareness.”

In 1994 Bristol University’s Interface Analysis Centre declared: “Provided the watch has remained in a normal environment, it would seem likely that the engravings were at least several tens of years of age…it is unlikely that anyone would have sufficient expertise to implant aged, brass particles into the base of the engravings.”

Hmmm. So the words and letters could be more than a century old.

The tangled web has encouraged some to think Florrie’s infidelity drove James Maybrick homicidally mad.

That said, why would a serial killer scratch damning evidence into his watch? Imagine you’re James Maybrick on a crowded train from London to Liverpool Lime Street. The passenger in the next seat asks you for the time so you take out your timepiece and flip open the cover.

“It’s a quarter before five,” you say.

“Many thanks.”

“You’re welcome.”

“Nice watch.”

“Thank you.”

“Good Lord! You’re Jack the Ripper!”

Of James Maybrick’s golfing ability nothing is known, but he was a keen horseman and rower, while he and Florrie were also members of Liverpool Cricket club. Sport was very much a passion, and therefore it’s unsurprising he became a member of Royal Liverpool in 1872 - especially when his love of all things horses, including betting on them, meant the Hoylake links, then shared with the Liverpool Hunt Club and home to a race course, were a source of two great pleasures.

A newspaper cutting dated August 7 1872 and neatly pasted in a Club scrapbook, reveals that in the Summer Meeting, competing for a gold challenge medal donated by John Dun, James Maybrick played with a George Scott. Neither of them won one of the many prizes and their scores that wet and windy day remain unknown. The Dun Challenge Cross is still played for today; back then the winner was scratch golfer Mr. J. C. Bald of London, with a score of 93.

One of James Maybrick’s greatest friends was Robert Cheshyre Janion - whose nephew, Harold, would become the flamboyant and influential Secretary of Royal Liverpool at the start of the 20th century. Both Maybrick and Harold Janion were present at Robert’s funeral in Halewood in August 1881.

James Maybrick had resigned from Hoylake in 1875 and, according to some, became a brutal killer 13 years later. True or not he will always be associated with Jack the Ripper - just type his name into a search engine.

Will Jack’s real identity ever be established? Put it this way, we can be sure the Maybrick family motto is meaningless in this context. Tempus omnia revelat. Time will reveal all n