Frederick Guthrie Tait was a fine sportsman. He played football for Edinburgh Wanderers and Edinburgh Academicals, but made his name on the golf course. His first introduction to the game was at the tender age of five while on a family holiday in St. Andrews. His natural talent was plain to see.

Freddie Tait was born in Edinburgh in 1870, the son of Professor Peter Guthrie Tait, a proficient golfer, noted mathematician and chair of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University. Freddie took full advantage of a privileged education at Sedburgh School in Cumbria and secured, all be it at his second attempt, a commission to the Royal Military School, Sandhurst, in Kent.

Though golf was a well established game in Scotland in the 1880’s, it was still a relatively new pastime south of the Tweed. Freddie would introduce the game to Sandhurst, and the Army’s strong commitment to sport gave him the time and space to perfect his game. He would soon be known as one of the game’s longest hitters. As Horace Hutchinson, the two-time Amateur champion, described him, he would ‘delight in letting the ball just have it’.

He would soon be known as one of the game’s longest hitters.

On his 23rd Birthday – Jan 11th, 1894 - when playing the Heather hole on his home course of St Andrews, he set a new world record by driving his ball a full 250 yards in flight and a total distance of over 340. Despite being aided by frosted greens it was a remarkable feat for a hickory golfer playing a gutty ball.

Tait’s distance was achieved more by excellent technique than brute strength, for his swing was not noticeably long. He would take the club back slowly under deft control and finesse, but, on the follow through, would steer the clubhead to a full finish with his weight perfectly balanced on his left leg. Grace and power were beautifully blended. Significantly though, on the rare occasions his driving failed him, he also had the ability to pull off miraculous recoveries.

In time Professor Tait would use his son’s prowess to test his theories on the aerodynamics of the golf ball in flight.

Throughout his career Freddie revelled in challenges, once taking on a bet that he couldn’t play from Royal St. George’s to the neighbouring Royal Cinque Ports - a distance of 3.2 miles - in less than 40 teed strokes, all with the same ball. He achieved the feat in just 32 blows. Unfortunately, his final shot crashed through a clubhouse window, incurring the wrath of the destination Club and wiping out most of his winnings.

By 1890 he had joined the Leinster regiment and then, four years later, the Black Watch where he was promoted to Lieutenant. A proud Scot, he saw it as his purpose in life to serve his country, but it was on the golf course where he fought his early battles.

In 1891 he entered his first Amateur Championship. Between 1893 and 1895 he reached the semi-finals on each occasion. It was a foretaste of things to come. In 1894 he posted a then record score of 72 at St. Andrews, an impressive feat, but it was in 1896 when he finally rose to the top. A 3rd place in The Open championship was followed by victory over Hoylake’s Harold Hilton in the final of the Amateur at Royal St. George’s in Kent by an imposing margin of 8 and 7. Scotland could at last acclaim their prodigal son, for there were few who embraced the fighting spirit of a proud nation quite like Freddie Tait.

Course records at Muirfield, North Berwick, Ganton, Blairgowrie and Morton Hall soon followed, but it was matches against Hoylake greats John Ball and Harold Hilton with which Tait became synonymous. Almost without exception he got the better of Hilton, but John Ball proved a far sterner test. By 1898 Ball had already notched up four Amateur victories, so when the Championship returned to Hoylake few had Freddie down as favourite. Surprisingly and disappointingly for the locals that year Ball was knocked out in the early rounds. Tait, on the other hand, was on a roll. After being on the winning side of five rounds of match play he had secured his place in the final.

He prepared in the most unusual way. The night before the contest the residents of Hoylake’s Market Street were entertained till the wee small hours by the rousing tones of Tait’s bagpipes as he paraded, playing full gusto, dressed in his clan’s tartan.

He was invincible the following morning, trouncing Samuel Mure Fergerson, a fellow Scot, by the commanding margin of 7 and 5.

The following year, 1899, brought Freddie’s greatest contest with arch-rival John Ball. Defending his Amateur title at Prestwick, Freddie was firm favourite. Anticipation quickly rose for yet another grand final when the two masters appeared on separate sides of the draw. By the following Saturday, the 2000 fans’ dreams had come true as the duellists went head to head.

It was matches against Hoylake greats John Ball and Harold Hilton with which he became synonymous.

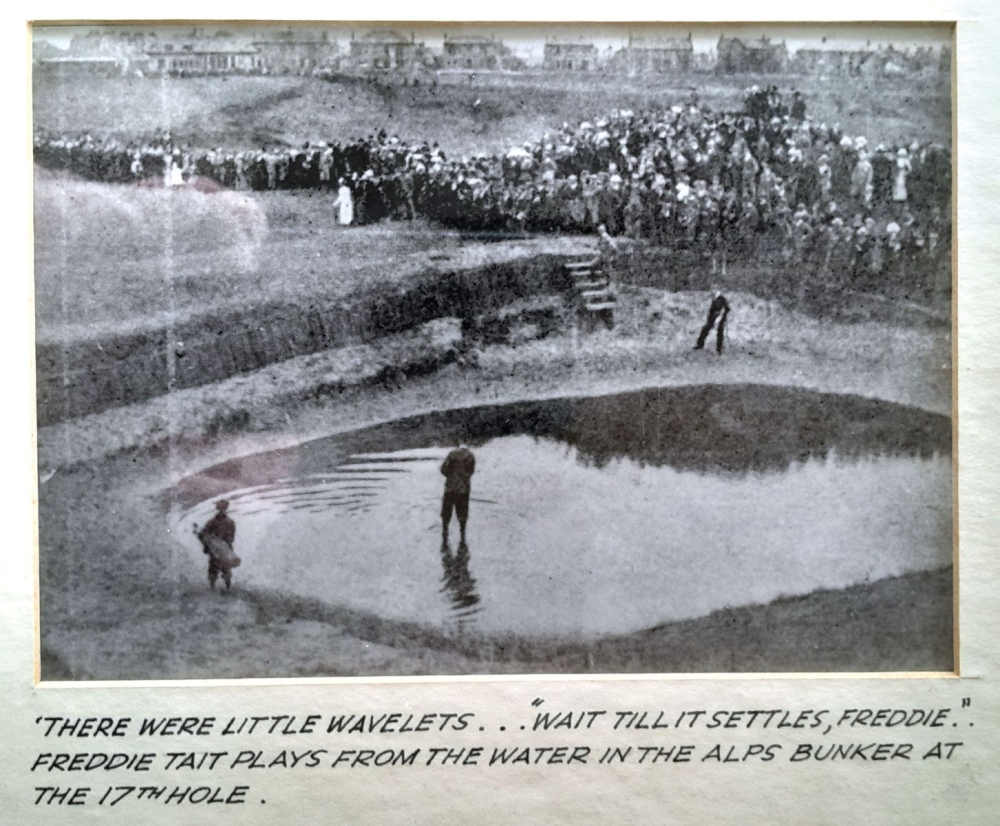

Weeks of heavy rain in the months before the Championship had left the course sodden and playing long. Many of the bunkers were full of water. As the players approached the 17th Ball was one up. The onus was on Freddie to attack the green, not an easy prospect when facing a blind shot and a long carry over the towering Alps. Loud groans told the story of how his second found a watery grave in the bunker, now a lake at the front of the green. Tait was given hope when Ball’s approach settled in the wet sand at the bunker’s revetted face. As Tait waded in and the ripples settled, the crowd fell silent. Moments later raucous cheers greeted what is now hailed as one of the greatest shots in golf. Remarkably, he had - literally - splashed out from a floating lie safely on to the green. However, within no time, Ball had matched him. Two putts apiece later the players halved the hole.

Freddie won the next and took the match up the 19th. But disappointingly for his many fans, Ball finally took the honours by holing a bold eight footer on the first play-off hole. It was a match Bernard Darwin would later call ‘the greatest, the most prostratingly exciting of them all’.

Sadly, within 18 months the whole golfing world was thrown upside down. Britain’s desire for South Africa’s precious minerals triggered war. As an enlisted soldier with the Black Watch, Tait was called up. On 24th October 1900 he boarded the SS Orient from London’s Tilbury Docks bound for the Cape. Less than six months later, Ball, now a volunteer in the Denbighshire Yeomanry, followed. 5000 miles away from the peace of Britain’s green and pleasant fairways the world’s two greatest amateur golfers now faced a far more dangerous and common foe, the aggrieved Boers resisting British occupation.

Though Ball would return home, Scotland’s golfing idol did not. After surviving a severe wounding in the early days of the conflict, Freddie Tait made his way once again to the front line and saw his final action.

On 7th Feb 1900, leading a charge at Koodoosberg Drift, he was shot and fatally wounded. Scotland went into deep mourning. It was almost inconceivable that this proud Scottish soldier would never see his homeland again, nor grace the fairways of the golfing world where he had once been ‘king’.

After burial close to where he fell on the battlefield, his remains were later re-interred in the West End cemetery at Kimberley in the Northern Cape.

Freddie Tait was unique in many ways. As a golfer he naturally endeared himself to the crowds through his patriotism, humility and charisma. His game was bold and powerful, his style dashing and fearless, his demeanour gracious.

His death was a tragic loss to Scotland and its national game. One can only wonder what he could have achieved had his life not been cut short.

At St Andrews, the R&A members were quick to commission a full-length portrait of Tait complete with his faithful dog Nails. It still hangs there to this day. In South Africa his achievements are marked in a different way. Each year at their nation’s Open Championship, the Freddie Tait Cup is awarded to the leading amateur who makes the cut.

Freddie’s memory lives on.